Modi’s Challenging Mandate

India’s election results ended a decade of single-party dominance in its domestic politics.

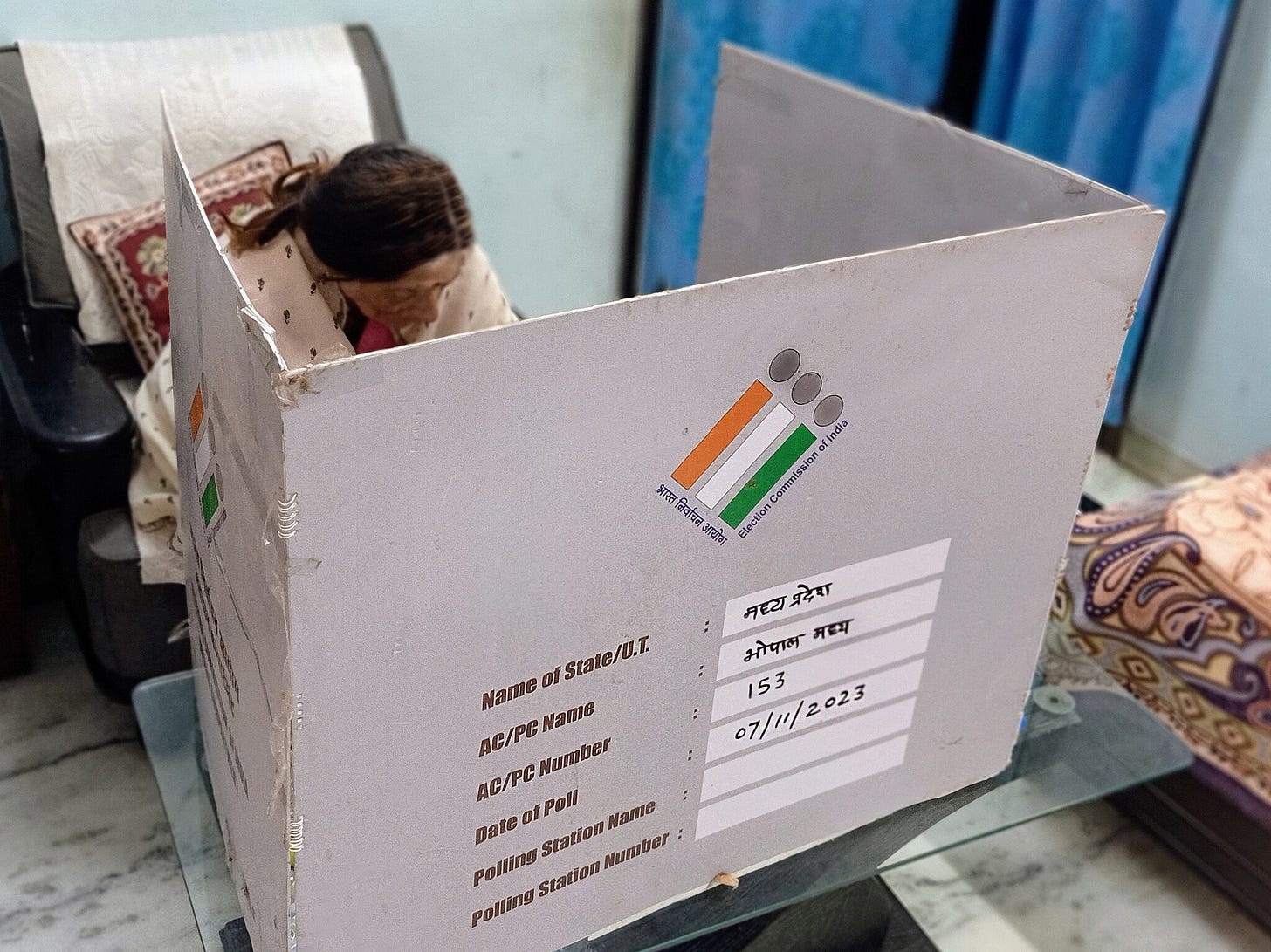

India’s 18th Lok Sabha election results have brought the Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) back to power for the third time in a decade. The elections took place in seven phases, across 44 days, to elect 543 Members of Parliament from 28 states and eight union territories. There were approximately 968 million eligible voters, out of whom 642 million people cast their ballots, making it one of the largest democratic exercises in the world. The ruling coalition garnered 293 seats, down from the 360 seats it had won back in 2019.

The opposition Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA) managed 232 seats, while 16 seats went to candidates and parties contesting independently from either alliance. People of Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim and Odisha simultaneously voted for their respective state assemblies, while the by-elections for 25 vacant constituencies were also held.

Unpacking the mandate

After a decade in power, the anti-incumbency factor is creeping in, as the BJP’s electoral appeal is diminishing among the voters. The party garnered only 240 seats, a significant down-turn from the 303 seats it had won in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. It won the majority of seats in Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Chattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha and New Delhi, but also severely suffered in many of its previous strongholds, including in the highly contested Uttar Pradesh. The results will especially reflect poorly on Narendra Modi, who had given lofty assurances of securing over 400 seats during his election campaigns. Nonetheless, he will lead the government for the third time, a record to be shared with India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

Despite losing the elections, the opposition alliance managed to gauze the national pulse. Besides questioning the BJP’s Hindutva ideology, which has polarised Indian society and polity, the alliance’s strategy to localise its campaigns and electoral agendas has strongly resonated among voters across different states. Three major issues merit special mention: First, the opposition strongly raised the issue of high unemployment rates during its election campaigns. India’s unemployment rate hovered between 6.5 to 8 percent in the last three years, a significant increase from 5.4 percent in 2014 when the NDA came to power.

The other prominent issue raised by the opposition during the election campaigns was the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for the farmers. This issue has been a bone of contention between the government and the farmers, who constitute roughly 55 percent of the country’s 1.4 billion population. Last year’s farmer’s protest across Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh would have significantly impacted the election results in these states, where NDA suffered heavy losses.

The third issue the opposition raised, which could have turned the BJP’s electoral prospects, is that of the Agniveer scheme the NDA government launched in 2022. The opposition accused the ruling party of designing the short-term recruitment scheme to deny pensions to the Indian Army soldiers. Because the scheme targeted the younger recruits of the lower ranks, it can be assessed that it would have antagonised India’s large sections of the young population aspiring to join the forces.

What comes next?

Both the ruling and opposition alliances celebrated the results, interpreting it as their “electoral victory”. While returning to power for the third time is no small achievement in the world’s largest democracy, BJP top-brass will be seriously worried about the erosion of their vote base in what it considers to be a “Hindu heartland” state. The regression in Uttar Pradesh, which has the highest number of Lok Sabha seats, proved particularly damaging for the BJP-led alliance. In the 2019 Lok Sabha polls, the coalition won 64 out of 80 seats in the State. It has now been reduced to a mere 36 seats.

The poor results in UP surely bring the leadership of powerful BJP politician Yogi Adityanath under the scanner, especially when the current chief minister is also being seen as one of Modi’s potential successors. Although Modi himself has managed to secure a comfortable victory from his Varanasi constituency, he could also come under pressure from party dissidents and aspiring successors who have so far been silent due to the prime minister’s national and international appeal.

On the other hand, the INDIA alliance has managed to secure respectable numbers, but will still face an uphill task at their opposition desk. The largest party in the alliance, the Indian National Congress, has managed 99 seats and will struggle to mount pressure on the government without strong support from its coalition partners. However, its fiery leader, Rahul Gandhi, a scion of the powerful Gandhi family, has been vocal in his criticism of the prime minister and his government.

It can be expected that Gandhi will continue his “Bharat Jodo Yatra”, a nationwide campaign to reconnect with the electorate while keeping the Modi government on its toes inside Parliament. This is healthy for the Indian democracy, which lacked a strong voice of opposition in the past 10 years. Even the fact that the regional parties like Samajwadi Party of UP, Janata Dal-United of Bihar, All India Trinamool Congress of West Bengal, Telugu Desam Party of Andhra Pradesh and Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam of Tamil Nadu performed strongly for their respective alliances, is encouraging, and points towards increasing regional influence in Indian politics.

Externally, the Modi government will continue to face a tough international climate it had been dealing with before the elections. India’s diplomatic relationship with the West, which had strengthened through strong economic, cultural and security partnerships, has been strained over the past year in the wake of the Ukraine war and India’s alleged covert operation against the Sikh separatists living in the United States and Canada. Modi will also face the challenge of restoring normalcy to his country’s relationship with strategic allies, which is key to New Delhi’s efforts to contain China’s increased ambitions in South Asia.

Regionally, the BJP’s return to power will relieve Bangladesh’s Sheikh Hasina government, which has faced its share of international condemnation for its poor human rights record and a crack-down against its political opposition. On the other hand, the relationship with the Maldives is far from normal under the new Mohamed Muizzu government in Male, which will test Modi’s foreign policy in the Indo-Pacific region. The relationship with Sri Lanka and Nepal has improved but will require close engagement and incentives that reflect Colombo and Kathmandu’s developmental ambitions.

Summing up, the Indian election results have ensured Modi’s third tenure in office will not be smooth sailing. Besides managing dissent within his party, he will have to gain the confidence of regional coalition partners and even reach out to the opposition camp when necessary to push through major policy agendas. It is unlikely the regional and global climate will be favourable to him either.

This op-ed appeared in the Kathmandu Post’s June 6, 2024 edition.

Thank you Anuragji for this well written piece. It is a good read. And it is a great win for democracy!